In collaboration with Bonkolab (childrens cancer research lab at Rigshospitalet), I supported Shape Robotics in creating a robotic avatar that would help children being absent from school, gaining a feeling being present at their classroom

My role

User research, prototyping, interaction design

Product direction

Contribution to affect design field

Contribution to theory of telepresence artifacts

Results

Design proposals (prototypes) for optimized remote human-to-human contact between children

Model of Affective Interaction (Lottridge et al.) — adapted for remote human-to-human contexts

Optimizing hardware specifications proposals

The treatment of children with cancer is more successful than ever.

Advances in technology and medical science have made it possible to detect and treat the illness more effectively. However, this progress often results in children being hospitalized for extended periods, leading to prolonged separation from friends and classmates. In recent years, there has been increased focus on mental health within this field, sparking new collaborations aimed at supporting the emotional and mental well-being of children during their treatment.

Enabling children undergoing cancer treatment in becoming a part of their classroom through emotional presence.

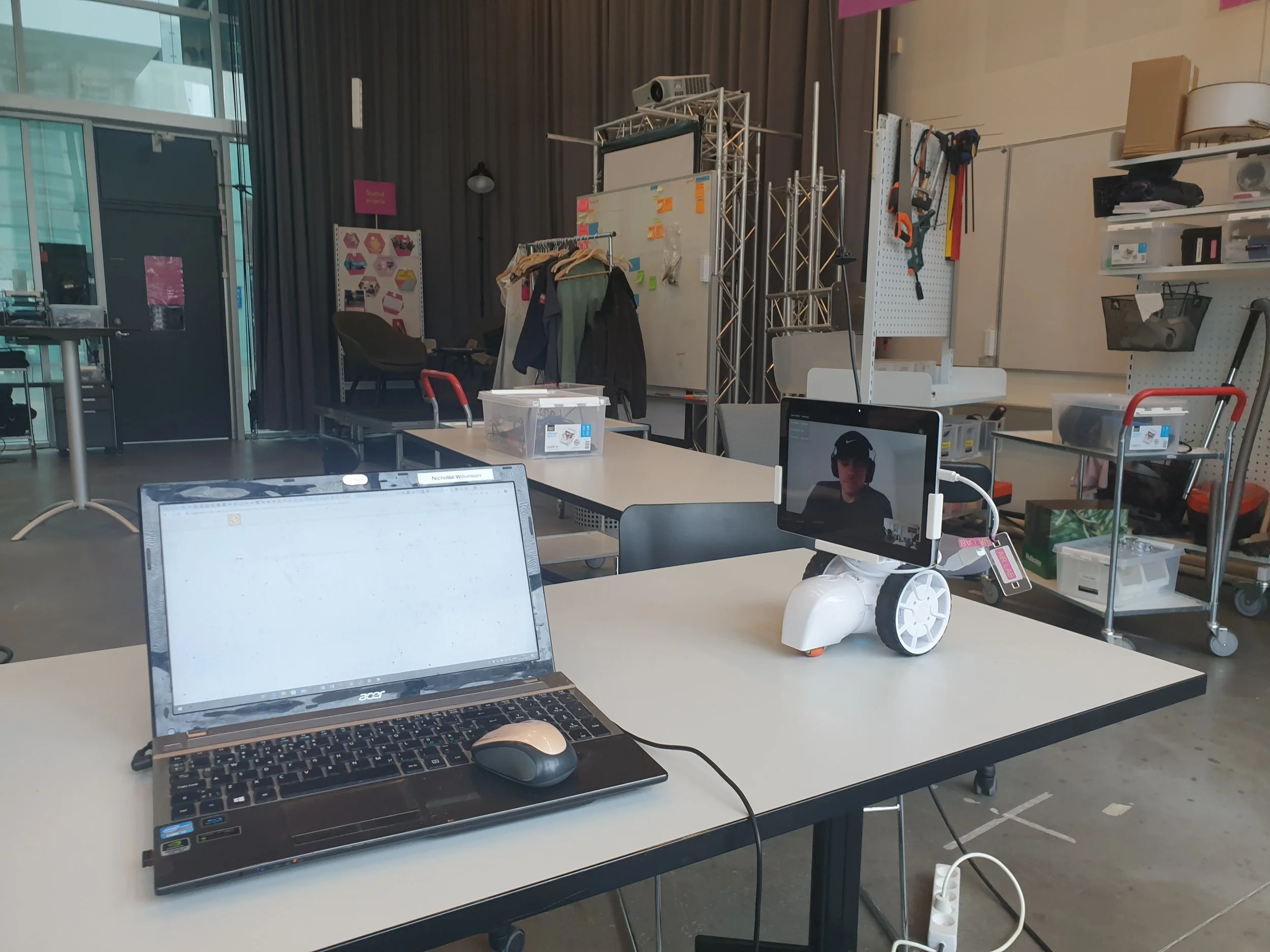

As part of my master’s thesis at the IT University of Copenhagen, I partnered with Shape Robotics and Bonkolab at Rigshospitalet to explore how telepresence robots could help children undergoing cancer treatment stay connected to their school communities — socially and academically.

These children face long-term school absence, leading to isolation, loss of identity, and difficulty reintegrating. Our aim was to support emotional presence, not just technical connectivity.

I designed Fable connect, a telepresence robot, in collaboration with Shape Robotics to support children with cancer in staying connected to their classmates during treatment. By enabling children undergoing treatment at hospitals to participate in real-time classroom activities with teachers and peers, we would be able to support their emotional and academic well-being (Bonkolab, 2019).

My main task was to create a strong sense of presence in the classroom of the child otherwise being absent and helping both them and their classmates coping with their illness.

Problem statement

”Children undergoing cancer treatment are often isolated from their school environment. This affects both their academic performance and their social identity. Current telepresence robots lack emotional nuance (e.g. facial expressions) to maintain meaningful peer connections, meaning the potential for “feeling of presence” is severely limited.”

Design challenges

The existing product — built for function, not feeling — lacked emotional nuance. During the exploration phase of our project we uncovered several knowledge gaps. After discussing the gaps with the engineers at Shape Robotics we decided to focus on the children (ill and healthy) as the primary users for the remote interaction, while still considering the social dynamic with other peers and teachers.

To focus our approach, we narrowed our research down to the following:

1: “Analyze the use of the telepresence system product through the goggles of affect theory to understand the limitations, challenges and opportunities that happens in a classroom setting with children”

2: “Understand what children going through cancer treatment need to feel as a part of a classroom”

Research approach

To uncover how a telepresence robot could genuinely support social connection in a classroom, we began by immersing ourselves in the environment it would inhabit. Through a series of autoethnographic tests, we simulated the experience of isolation and observed classrooms both with and without the presence of a robot avatar. This allowed us to see how its introduction shifted group dynamics, attention, and interaction patterns.

Alongside these observations, we conducted in-depth interviews with the primary users: children in primary school. We spoke both with those operating the robot remotely and with their classmates physically present in the room. These conversations revealed the subtleties of how presence is felt—or not felt—through a telepresence device.

To ground our understanding in expertise, we interviewed specialists from multiple fields: engineers from Shape Robotics, health professionals including cancer treatment specialists at Rigshospitalet, and teachers who interact with these children daily. Their insights helped us map the current challenges, the practical constraints, and the opportunities that had already been identified in earlier iterations.

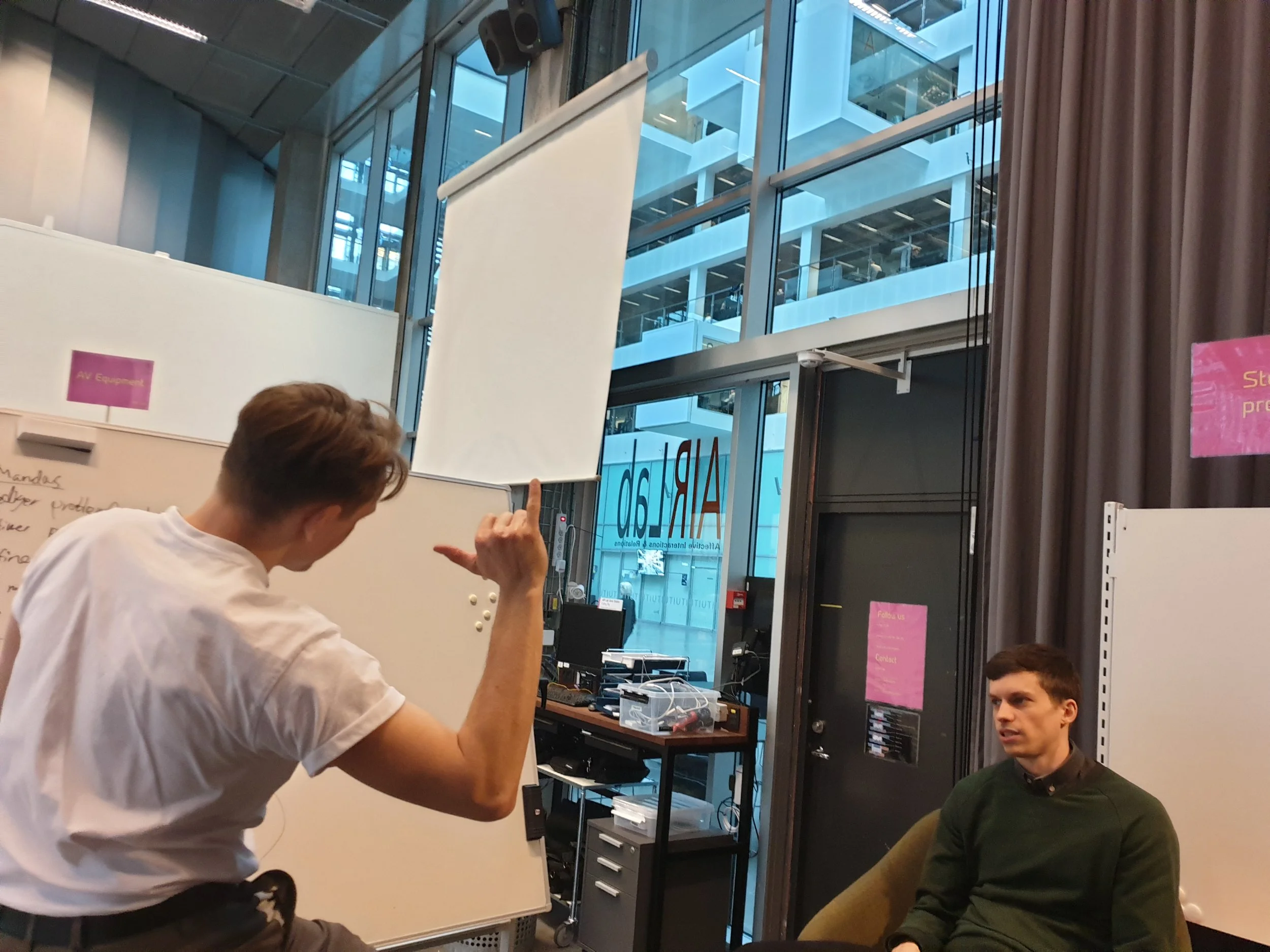

Exploring how body language effects a conversation

Exploring how a lack of body language effects a conversation

Key findings

Lack of ‘feeling of presence’ leads to children becoming emotionally detached.

For the children in treatment, school was more than a place to learn — it was a vital connection to their everyday lives. Yet, extended absence often left them feeling detached from their classmates, eroding both their learning and their sense of belonging. What stood out most was their deep desire to remain socially present in the classroom. For many, the chance to share moments, jokes, and conversations with peers mattered even more than keeping up with assignments. This social link not only helped maintain friendships but also fostered a renewed motivation to learn. At the same time, we observed a tendency toward emotional withdrawal: many children simply lacked the energy or emotional bandwidth to take the first step in reconnecting, which in turn reinforced their isolation over time.

The existing interaction demanded product-experience and more intuitiveness.

For teachers and classmates, the presence of a telepresence robot introduced its own set of challenges. Many classmates were unsure how to engage with the child on the other side of the device, often defaulting to overly formal or passive forms of communication. Teachers, meanwhile, described a difficult and delicate balance between treating the absent child as they would any other pupil and showing the visible sympathy their situation seemed to demand. The result was a subtle, persistent awkwardness in classroom interactions.

This led the consequence of existing telepresence setups tended most of the time to create a one-way connection: they allowed the remote child to observe classroom life, but also offered a few opportunities, such as group assignments, for classmates to actively interacting with the robot and make the child feel truly included. The experts at Bonkolab told us that the children undergoing treatment were severely energy-deprived making it that more important to create intuitive experiences that work the first time.

Potential for succesful communication/interaction is lost through bad connection.

Our observations also revealed how delicate the sense of presence can be when mediated through a robotic avatar. Even minor technical limitations such as a slight delay in sound, limited mobility, or a lag in movement were enough to disrupt the fragile illusion of co-presence. At the same time, we found that seemingly small gestures had an outsized impact. A simple turn of the robot’s “head” or a quick wave could dramatically change how noticed and acknowledged the remote child felt. Most importantly, we learned that being seen was not the same as feeling included. True connection required active emotional feedback from peers — a glance, a smile, a shared joke — to bridge the gap between visibility and belonging. However, to have potential for actual succesful interaction/communication — being able to gesture, joke, etc. the connection needed to be without issues as this quickly led to peers losing interest.

We applied and adapted established affective interaction models to analyze our findings. By combining theory with the qualitative data from classrooms and expert interviews, we were able to shape a set of actionable UX recommendations that guided the next steps of the robot’s development — shifting its role from a simple avatar device to a potential bridge for emotional connection.

Outcomes

We contributed to both the development of Fable Connect but also to the field of telepresence which became

We developed design proposals for enhancing Fable’s affective expressiveness, such as:

Personalized robot appearance to strengthen attachment

Gestural expressiveness

Configurations that supports a need for privacy

We development and hardware priorities:

Focusing on improving social aspects of the interaction rather than academic proficiency, have the potential to increase motivation for being active at school over distance

Updated speaker software & hardware (client side) to automatic switch and prioritize between proximity and distance chatter

More effective wifi-recievers to limit lack of connection as this makes the children (classroom side) avoid the robot

I extended 2 key models and contributed to pediatric use of telepresence artefacts:

Model of Affective Interaction — adapted for remote human-to-human contexts, introducing a new layer of “properties of connection”, that helps analyzing how ping and the lack of connection impact a conversation over distance

Model of Affective Means — revised to separate social robots from telepresence systems

Redefined the role of telepresence in pediatric care from "remote access" to emotional mediation

Model of affective interaction adapted for remote human-to-human contexts

Reflections

While testing, it became clear that research through artefacts is the most effective way of learning new fields

This project taught me how to design with empathy under heavy constraints — both ethical and situational. It was a deep dive into the intersection of design, emotion, and health tech, and showed me how even complex theory can lead to actionable, human-centered design when rooted in real user needs.

We managed to support the development at shape robotics by:

Delivering actionable design recommendations to Shape Robotics for future iterations

Implementing the concept of affective telepresence into the product

Strengthening the case for emotionally intelligent design in assistive tech for children

Highlighting the limits of perception-only models in UX for emotionally sensitive contexts

Contributing data with auto-ethnographic research in a highly constricted period of time (Covid-19)